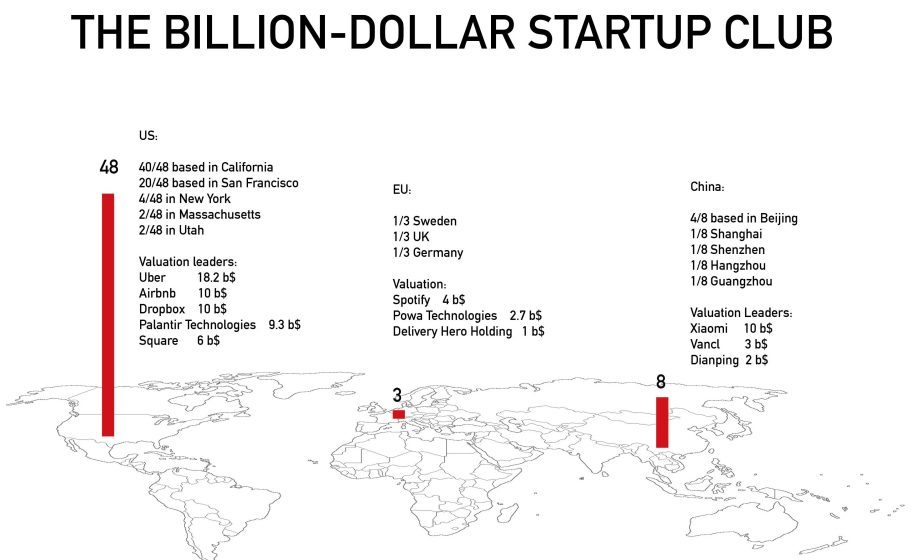

The Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones VentureSource recently started publishing a list of companies that are valued at $1 billion or more by venture-capital firms.

Here it is in graphical format (credit to J.Peng).

The qualification criteria for the club are: privately held companies that have at least VC firm in the capital and have raised money in the last three years. Companies that were majority-controlled by an institutional shareholder or represent secondary deals are excluded.

The data confirms what many members of Europe’s startup ecosystem suspected, yet seeing it in printed form somehow stings more. Of the 59 companies in the BDSC today, a mere 3 hail from Europe. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority are U.S. companies (mostly from California), but China alone boasts almost 3 times as many companies as the whole of Europe.

Why so few European unicorns ?

First, my apologies for employing the insufferably overused term unicorn. I would argue that until we can stop calling them unicorns they will continue to not exist (note: excellent joke I read on Twitter the other day: Q: what is the plural form of the word ‘unicorn’? A: ‘portfolio’).

Anyway, consternation and speculation abound on the reasons for this dearth of billion dollar babies in Europe. Here are my thoughts:

- VC in Europe is still relatively nascent compared to the U.S. (remember the Silicon Valley of innovation and VC started back in the 1950s).

- Europe is not a homogeneous region like the U.S. or China, but rather a diverse collection local countries, each with their own set of macroeconomic issues, regulatory hurdles, or well-intentioned but misled policy (sometimes all of the above!).

- A chronic, across-the-board lack of sufficient late-stage financing sources.

- An inherent cultural tendency toward risk aversion.

- Perhaps as a result of the above two points in particular, a VC practice of deploying smaller investment tickets, which often translates into undercapitalized startups or companies railroaded into profitability over growth earlier in their cycles.

The three European companies that made the list — Powa, Spotify, and Delivery Hero — have several things in common. All have raised raised multiple and increasingly large rounds of funding (3, 7, and 9, respectively), and all raised from historically tier-1 VCs like Accel, Kleiner Perkins, Northzone, and Wellington. All three have ambitions beyond their domestic markets. They also prioritized growth over profitability for far longer than a typical European startup.

As for the future, a variety of forces are at play, yet net-net hopefully give some grounds for cautious optimism that more European companies will enter this club. The new generation of European entrepreneurs demonstrate global ambitions and the innate ability to transcend boundaries. A handful of European VCs are starting to crush the small ticket philosophy — Index Ventures, Northzone, and Accel come to mind — which I submit reflects a greater theme of 99/1 is the new 80/20. Strong regional infrastructure like data pipes and physical rails fosters innovation. Finally, to invoke Jean Paul Getty: a billion dollars ain’t what it used to be. I expect this club will grow in membership.